If there is one economic indicator that is most used as a measure of economic health, it is the unemployment rate.

Many people think they know about the unemployment rate. Are you one of those who’d be surprised you may have more to learn? Read on to find out.

In this blog post, the BBER dispels four common misconceptions about the unemployment rate, in a simplified manner, to give you a leg up in interpreting next month’s news cycle.

Misconception #1: The unemployment rate is a measure of the number of people without a job

Question: Which of the following people would be counted as part of the official unemployment rate?

- Jim: A stay-at-home dad who has been out of work since September, when he chose to take over childcare duties.

- Patty: A marketing and graphic design professional who has been receiving unemployment insurance since losing her job last month. But she’s been freelancing for about 10 hours each week while she looks for a permanent position.

- Angela: An X-ray technician who lost her job early on during the pandemic. She looked for a new position for about six months before giving up her search.

- Dave: A recent college graduate who hopes to find a job in mechanical engineering, but he is waiting to begin his job search until later this year.

Answer: It might be surprising to know that none of the individuals described above would be counted as unemployed, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistic’s official measure.

That’s because, when it comes to the official unemployment rate, there is a difference between not working and being unemployed. To be officially counted as unemployed (and included in the unemployment rate), a person must be willing and able to work and to have looked for a job in the past four weeks. Only people meeting these strict criteria—together with anyone currently working (either full-time or part-time)—are counted as part of the labor force and included in the calculation of the official unemployment rate (measured as the number of unemployed people as a percentage of the labor force).

Misconception #2: The unemployment rate is a measure of the number of people receiving unemployment benefits

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, Minnesota’s unemployment rate was 2.5% in March 2022, the lowest rate the state has experienced since 1999. This means that of the 3.1 million workers included in the state’s labor force, 76,000 people were counted as unemployed. By comparison, fewer than 60,000 people filed unemployment insurance claims in March. There are a couple reasons for this discrepancy.

First, it is important to know that eligibility for unemployment benefits is based on previous work history and the benefits are available only for those who have been recently laid off. By comparison, the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) counts the number of unemployed individuals using a monthly survey of randomly selected households. The survey counts anyone who is not currently working but has searched for a job in the past four weeks as being unemployed, not just those receiving benefits. Therefore, the survey captures individuals such as young people entering the labor force with no past work history, people who have been out of the labor force for some time and have recently begun searching for a job, or people who left their job voluntarily but have not yet found a new position.

Misconception #3: The lower the unemployment rate, the stronger the economy

Minnesota recently hit the lowest unemployment rate it has seen since 1999, but is this low rate really a good thing? While lower unemployment is usually regarded as a positive sign for the economy, this is only true to a point. The unemployment rate will never (and should never) reach zero, because some level of unemployment is natural and necessary for the economy to function. Most economists believe that the natural rate of unemployment (when the economy is at full employment) falls somewhere between 4% and 5%. Rates too far below that range can have a variety of negative impacts on the economy, including recruitment and retention challenges, lost productivity, and more. But one negative side effect of low unemployment is especially obvious in today’s economic climate: increased inflation. How does this happen?

- When workers are scarce (as they are right now), companies need to raise wages to recruit workers.

- Companies then pass a portion of the costs from higher wages to consumers in the form of higher prices on goods and services.

- Rising prices causes more workers to demand increases in wages to pay for the increased cost of goods and services.

- Companies must provide higher wages to recruit and retain workers.

- Repeat steps 2, 3, and 4.

The cycle described above, often called a wage-price spiral, is of such concern that many policymakers would prefer to have unemployment be too high than too low.

Misconception #4: The unemployment rate reported by news media is the most important economic measure to watch.

The great benefit of the unemployment rate is that it is calculated monthly for a wide range of geographic regions, including small geographies, such as states, counties, and cities. This makes the measure readily available and easy to use to compare regions. But there are some major limitations to the unemployment rate. As mentioned previously, many individuals—such as Jim, Patty, Angela, and Dave from our earlier example—are not officially counted as unemployed because they are working part-time or are not actively searching for a job. But given the right circumstances, people who have given up on a job search (discouraged workers), are not actively looking but might consider the right opportunity (marginally attached), and those who would like to work full-time but are currently working part-time because their hours have been reduced or they were unable to find full-time jobs (employed part time for economic reasons) could easily join the labor force or move to a full-time position.

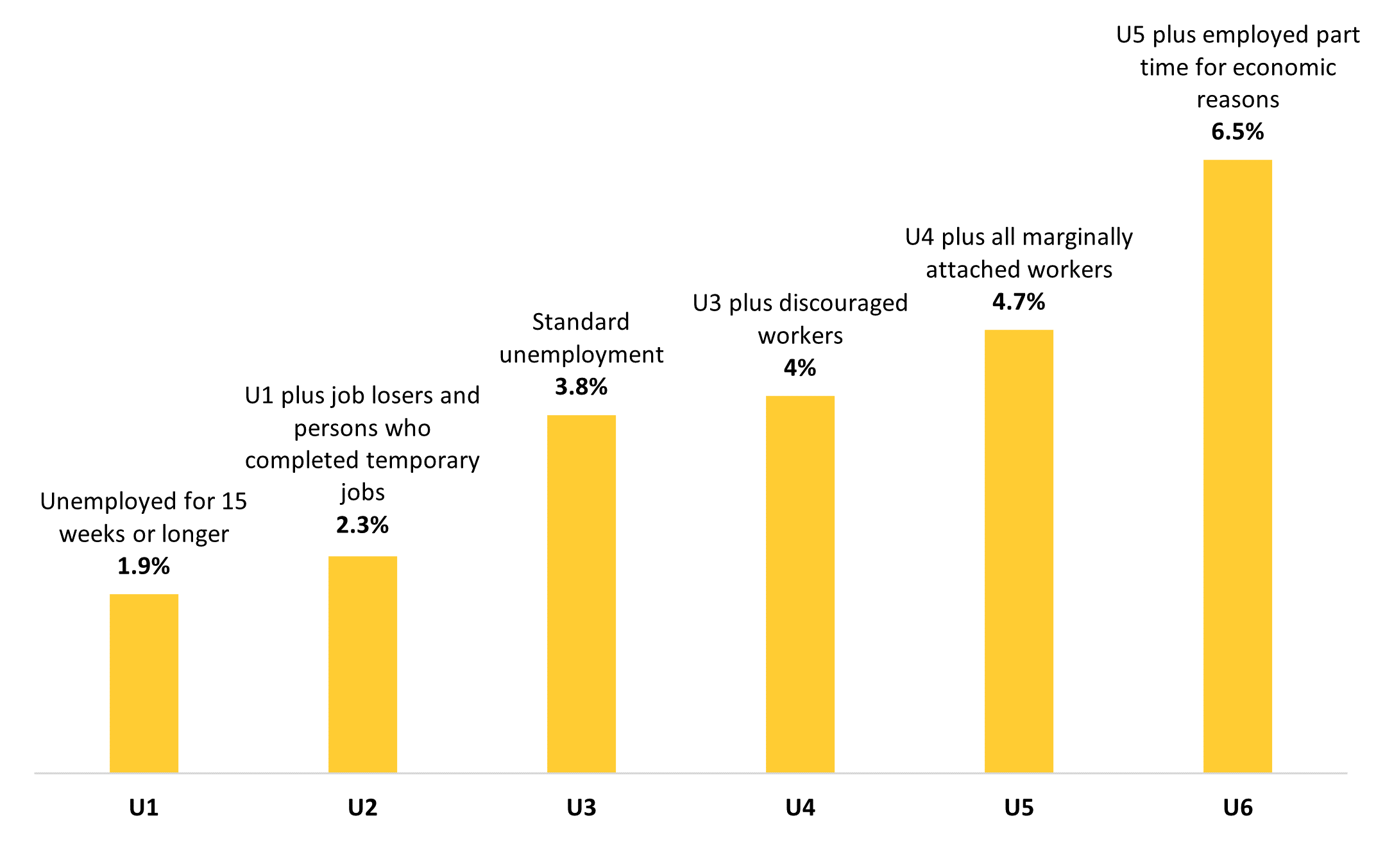

To better track these individuals, the Bureau of Labor Statistics actually calculates six unemployment rates. Figure 1 shows, for each of the six alternative measures of unemployment, the average unemployment rate in Minnesota in 2021. These alternative measures are additive, meaning U1 is the least inclusive group (including only people who have been unemployed for 15 weeks or longer), and U6 is the most inclusive, capturing all those traditionally measured as unemployed plus marginally attached workers, discouraged workers, and persons employed part-time for economic reasons.

SOURCE: Bureau of Labor Statistics

These measures can be incredibly useful to economists and policymakers to measure slack in the labor market. Namely comparing the broader U6 rate to the standard U3 can yield some interesting insights about the nature of the labor market. By including people who are not currently looking for work but might be enticed into the labor force under the right circumstances, we can better understand the size of the potential labor pool. As shown in Figure 1, the U6 unemployment rate was nearly double that of the standard rate in 2021, suggesting there are tens of thousands of people statewide who are not currently working but who might consider joining the labor force given the right opportunity.

Another solution is to focus on the number employed, rather than unemployed. Many economists prefer this method because there is less variability in who should be counted, and the results tend to be less misleading. This is especially true during economic fluctuations, such as the post-COVID recovery we’re currently experiencing.

Data for alternative measures of unemployment is readily available at the state and national levels. The link to state data also includes expanded definitions of each level and other information about the alternative rates. For more insight, check out the interactive chart of Minnesota’s U3 and U6 rates.